Media 1. Harp seal pup crying for mother.

I peek out of the ice cave where I had been huddled for the past few days, staring out at the vast expanse of grays and blues. Exhausted from crying, I feel numb as the reality sets in: my mother isn’t coming back. The sound of the cold wind among the creaking of ice speaks of loneliness, desolation. With the quiet hope that I will be woken up by the protective warmth of my mother’s breath, I close my eyes and try to sleep.

Media 2. Harp seal pup peeking out from ice cave.

Creeeeeaaaak. I startle awake. Alarmed, I roll onto my flippers, poking my head above the ice and sniffing the chill air for other creatures as I look around for the source of the sound. About four body lengths away, I see the dark blue line where a crack has appeared in my ice floe, and a sinister fizzing sound is emitted. As I watch, the dark blue line thickens as a chunk of my safe haven, my ice floe, slowly floats away. A panic rises up in my chest, and I pull myself to the edge where the ice had been, and find myself staring into the cold, black-blue depths of the ocean. I remember my mother’s worried pacing around this glowing white island of ice, and the similar creaking sound when we had broken off from an even larger sheet of ice more than a week before. She had mumbled about the lack of suitable nesting ice this year, nothing like the gleaming white ice fields of her adolescence, and about the lost pups of years past. She had turned to me with soft, sorrowful eyes, like the ones I imagined that she would have turned towards her children of previous years before leaving them, too, to float among the fragmented pieces of ice, to learn to swim before the protective ice broke up, or to drown.

*******

I’m shivering. Time has passed and my glowing white coat has mostly shed, replaced by a gray coat with dark splotches. I’ve lost weight and my protective blubber had dwindled during my weeks of inactivity, but recently, spurred by the inevitability of my dwindling haven, I’ve felt strong enough to venture into the water, paddling clumsily but with a fierce determination to learn how to swim as gracefully as the grown-up seals I see in the water do. Today, I’m determined to catch my first meal. I lug myself to the edge of the ice floe, and slip into the cold water. Submerged and floating in place, I listen to the water around me and feel the currents moving past my whiskers. Subtle perturbations in the moving water alert me to the presence of fish. Like I’ve seen older seals do, I dive deeper, faster and faster towards the school of food. Bursting in, I wildly gnash my teeth, attempting to catch one of the frantic darts of silver in my jaws. The effort is futile. I rise again, thinking quickly, trying to calm myself. My senses hone in on a small cluster of fish swimming confusedly amidst the chaos. With fierce determination, I gather myself. I dive again, locked on my target, getting closer, closer… YES! My jaws clamp around the squirming silver body of the fish. In jubilation, I rush to the surface of the water, searching for a resting place to enjoy my first catch. Spotting a sizable chunk of ice ahead, I head towards it and lug my body onto the unsteady surface. I bite into my catch, becoming acutely aware of my raging hunger as I swallow the first mouthful of sustenance since my mother’s departure. Finished and galvanized by the thrill, the satisfaction of a successful hunt, I gather myself again to dive back into the ocean to search for more food.

Media 4. Juvenile harp seal swimming.

A desperate cry coming from a nearby ice floe stops me. Holding myself still against the shivering wind, I listen closely. A few minutes of just the roar of the wind, and then the cry pierces through again–a cry much like my own, when mother had first left. I slide into the water and head towards the sound, happening upon a dwindling patch of floating ice. Perched on top, with a look of terrified despair, is another seal pup, with spots beginning to darken on its molting coat. Old enough to be without her mother for a few weeks, but certainly not old enough to have learned how to swim any substantial distance. The water around me seems to grow colder as I recall my mother’s mumblings about the demise of my little sister the year before. Staring into the other pup’s eyes, I imagine the eyes of another with a face similar to my own, those of my sister as she waited, stranded, for the ice to melt around her to deliver her unto the dark depths–and when the last pieces of the ice finally broke, leaving her to beat the water around her desperately with small flippers, struggling to float, to live, for a few more minutes before energy and breath succumbed to the freezing waters. There’s nothing I can do. My own stomach rumbles, and my own survival is at stake unless I learn to feed. Giving a returning, sympathetic cry, I dive back into the depths.

Media 3. Baby harp seal stranded on melting ice.

**************

Every year, baby harp seal pups like this one are born in the subarctic. In late January when the subarctic sea ice begins to form in pancake-like sheets, their mothers migrate to breeding grounds in northeastern Canada, eastern Greenland, and northwestern Russia[1] to choose the thickest ice floes as nesting sites to give birth to a single pup. After birth, the mother stays with the pup for 10 to 12 days, fasting and weaning her helpless pup. During this time, the pup triples its body mass, nursing on its mother’s fatty milk and developing a layer of blubber. Afterwards, the mother leaves the pup abruptly to return to mating and feeding. Alone, the abandoned pup fasts on the ice for up to 6 weeks, losing up to half its body mass before it learns to swim and feed on its own. [2]

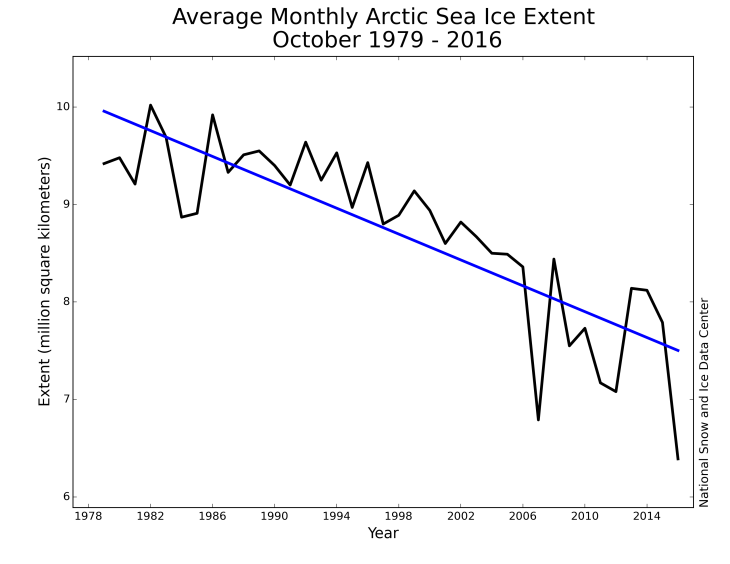

For centuries, baby harp seal pups have been prized for their soft snowy white pelts (“whitecoats”), and their exploitation continues to this day in the form of the annual Canadian seal slaughter. But in recent years, another obstacle has arisen against the seal pups’ survival. According to an article in Science, “poor ice conditions were more common in the past decade than in the preceding 30 years”[3] in the harp seals’ breeding grounds, making stable nesting ice scarce for pregnant harp seals during the breeding season. This is part of a larger problem of long-term arctic sea ice decline, attributed to increased levels of CO2 in the atmosphere, confirmed by both studies of climate models and studies systematically examining all possible contributing factors for decreasing sea ice coverage.[4] When increased atmospheric CO2, a greenhouse gas, traps heat near the earth’s surface, the warmer air and water near the arctic both increases the melting of multi-year ice and impedes the formation of new ice. The result is a dramatic downward trend in the Arctic sea ice extent in recent decades.

Media 5. Long-term sea ice extent decline. “Monthly October ice extent for 1979 to 2016 shows a decline of 7.4 percent per decade.”

Although “hundreds of thousands of female [harp] seals congregate on the floating ice to give birth in late February and early March”,[5] the long-term decrease in arctic sea ice can spell death for most the pups born. After being abandoned by their mothers and learning how to swim, harp seal pups are vulnerable to stranding and drowning when the ice floes they perch upon break apart and melt. As National Geographic reported, “without thick, solid ice expanses,” seal pups may also be “crushed by broken-up chunks of ice.”[6] In particularly iceless years, almost all the pups born in the spring may perish before summer, as evidenced in 2010, when “90 percent of the harp seal pups born in the Gulf of St. Lawrence are thought to have died due to lack of ice before Canada’s commercial seal hunt even begun.”[7]

Although the harp seal populations are still relatively plentiful, humans’ long history of exploiting the species has scientists worried about what the damaging effects of climate change would have on the future of the species. While proponents of the harp seal hunting often cite the species’ growing numbers in the past few decades, populations are merely recovering from “overhunting in the 1950s and 60s [that] had reduced the population by nearly two-thirds” in response to harp seal pup pelt bans by the EU and Russia.[8] Marine biologists such as David Johnson from Duke University recommends that humans take action now in order to avoid a “conservation train wreck” in the future, advising, “We should control what we can control. We can’t control the reproductive biology of seals, or where and how ice forms in their breeding habitats from year to year… What we can control is human behavior.”[9] This moderation of “human behavior” may take the form of slowing the long-term decline of arctic sea ice, or of reducing the number of baby seals massacred each year for political and commercial purposes, in order to save the harp seal and maintain the ecosystems of the arctic and subarctic.

Word Count without Quotes: 1432

Word Count with Quotes: 1582

Footnotes:

[1] Dave Mosher, “Baby Harp Seals Being Drowned, Crushed Amid Melting Ice,” National Geographic News. National Geographic Society, January 6, 2012, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2012/01/120106-harp-seals-global-warming-sea-ice-science-environment/. (accessed November 20, 2016).

[2] Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, 2nd ed. s.v. “Harp Seal”

[3] Erin Loury, “Baby Seals Need the Nicest Ice,” Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science, November 30, 2011, http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2011/11/baby-seals-need-nicest-ice. (Accessed November 20, 2016).

[4] National Snow & Ice Data Center.”What is causing Arctic sea ice decline?” NSIDC.com. https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/icelights/2012/05/what-causing-arctic-sea-ice-decline. (accessed November 20, 2016).

[5] Erin Loury, “Baby Seals Need the Nicest Ice.”

[6] Dave Mosher, “Baby Harp Seals Being Drowned, Crushed Amid Melting Ice.”

[7] International Fund for Animal Welfare, “Seals and climate change,” IFAW.org. http://www.ifaw.org/united-states/our-work/seals/seals-and-climate-change. (accessed November 21, 2016).

[8] Humane Society International. “Myths and Facts about Canada’s Seal Slaughter,” HSI.org. http://www.hsi.org/assets/pdfs/myths_and_facts_seal_hunt.pdf. (accessed November 21, 2016).

[9] Dave Mosher, “Baby Harp Seals Being Drowned, Crushed Amid Melting Ice.”

Media Citations:

- Harp seal pup crying for mother, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8QWQZnBDf68.

- Harp seal pup peeking out from ice cave, https://images.sciencedaily.com/2012/12/121230180804_1_540x360.jpg.

- Baby harp seal stranded on melting ice, https://images.sciencedaily.com/2013/07/130722123124_1_900x600.jpg.

- Juvenile harp seal swimming. http://www.thesealsofnam.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/749241.jpg.

- Long-term sea ice extent decline. http://nsidc.org/arcticseaicenews/files/2016/11/Figure3-1.png