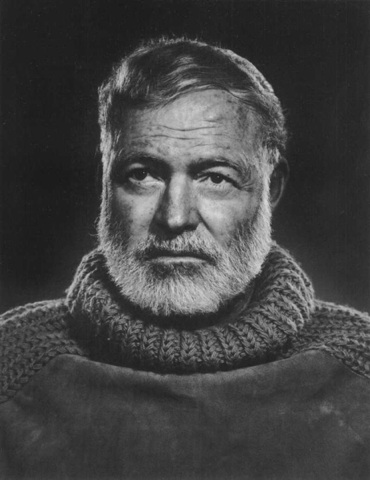

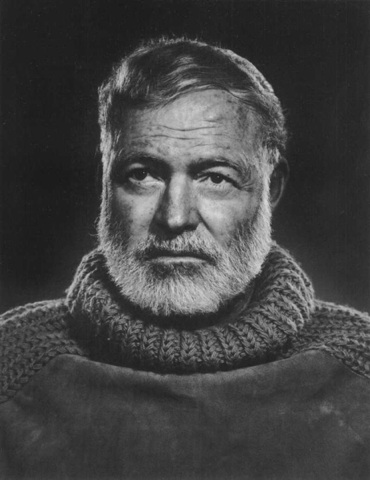

Paris Review: "How much rewriting do you do?"

Hemingway: "It depends. I rewrote the ending to A Farewell to Arms, the last page of it, thirty-nine times before I was satisfied."

Paris Review: "Was there some technical problem there? What was it that stumped you?"

Hemingway: "Getting the words right."

----------------------------------------------

The book's final sentence (the subject is the death of a friend):

"But after I got them to leave and shut the door and turned off the light it wasn't any good. It was like saying good-bye to a statue. After a while I went out and left the hospital and walked back to the hotel in the rain."

"Getting the words right" applies to every word, including even the little prepositions that accompany verbs. Concerning the latter, consider, for example, the phrase "My curiosity triumphed in convincing me": the best preposition would be "by" rather than "in." In the past you would know this automatically because of the amount of reading you had done, but now, apparently because many of even the best students don't read as much, you might have to look it up. Where would you look it up? In the kind of dictionary that gives detailed definitions and examples, such as the Oxford English Dictionary. If you were to look up the verb "triumph" you would see that using the preposition "in" is usually reserved for objects as in Shakespeare's "Which triumpht in that skie of his delight" and "triumphing in their faces." When you refer to an action such as "convincing," the most appropriate preposition is "by," as in Scott's "triumphed by anticipation over their surrender." When you use the "wrong" preposition the knowledgeable reader is halted in his or her reading and the effectiveness of your writing is weakened.

See how abstractions are the opposite of what is sought in writing in English courses.

Concerning dialogue: If you are deliberately making mistakes to make speech or writing more authentic you must follow each mistake with "sic" or I will assume the mistake is yours rather than the speaker's.

ADVICE FOR ACHIEVING BETTER WORD CHOICE

Adapted from John Trimble’s Writing with Style

by Adam Vramescu

The function of college writing is to convey a point as clearly and concisely as possible, without sounding too casual or too stuffy. Our working rule is “Don’t write anything that’s too formal or convoluted to say out loud, but not everything you say aloud is focused enough to commit to writing.” So how to achieve this clarity and conciseness?

Trimble lists five specific ways to serve your readers’ needs (8)

(or, five reasons your high-school English teacher was wrong):

Clarity is how clear your writing is, from the reader’s perspective (not your own).

Tests for clarity:

1. What does this sentence mean? Explain the sentence to yourself. If there’s a more direct way to say it, wouldn’t your reader appreciate hearing it?

2. Why/How? Have you explained the reason for each claim you make? Have you analyzed properly? (Ex: “Hamlet is Shakespeare’s finest work.” WHY??)

3. Like what? Are you being specific enough? (Ex. “The character of Hamlet displays the qualities of a tragic hero.” LIKE WHAT???)

Vigorous Verbs

Fact #2: Good prose is direct, definite. That’s a quote from WWS (56). Your aim is to cut to the fat and get to the point. Trimble uses the analogy of a handshake—a firm handshake inspires confidence, and so will direct prose. Remember, your goal is to make a successful argument—so sell yourself a little, will you? Meanwhile, vague writing (lots of passive voice, needlessly protracted sentences, empty intensifiers, expletives and impersonal constructions like “there is” and “it is”) is like a weak handshake.

This tip admits you into the secret writer’s club: “[T]he verb acts as the power center of most sentences” (57).

So remember that impetuosity/prudence sentence? Let’s check up on it: “Prudence now tempers his impetuosity.” Much better!

A note: Passive voice, expletives, and the like aren’t uniformly bad. There are situations where you’ll find them preferable, such as when the agent doesn’t matter, or when you’d like to soften your tone, or when you’re using it for emphasis, such as “Charles alone was injured in the accident” (57). But don’t let these be your default; use them stylistically. Tread carefully.

Freshness, WIT

EXAMPLES

“There is no deodorant like success.” –Elizabeth Taylor

“. . .the drama, which develops at about the speed of creeping crab grass. . . .” –John Aldridge

“He had an upper-class Hoosier accent, which sounds like a bandsaw cutting galvanized tin.” –Kurt Vonnegut

“Have I been toiling to weave a labored web of useless ingenuity?” –T.S. Eliot, after “several paragraphs of highly theoretical speculation.”

Writing becomes fun when we bring words to life. We have the opportunity “to delight our reader with arresting phrases” and images. Moreover, if you’re really playing the game, you’ll be able to surprise your reader (as Eliot did in the above quote). Trimble thinks of baseball: “A skilled pitcher mixes up his pitches. He’ll throw a fastball, then a curve, maybe a change-up, then a knuckleball. Skilled writers work the same way…feeding our appetite for…a fresh idea, a fresh phrase, or a fresh image” (59).

Secret writer’s club tip #2: Images and metaphors are your artillery against blandness.

“He wrote with a surgical indifference to feelings” –William Nolte

“A professor must have a theory, as a dog must have fleas.” –H.L. Mencken

Wow, a surgical indifference? The idea, here, is to search constantly for the perfect image. Or, as Trimble says, “Always be thinking in terms of ‘like’” (61). This is seriously advanced stuff, but if you’re up to the challenge, try to incorporate some images, metaphor, or wit into your papers.

Remember, of course, that freshness is not synonymous with humorousness, and you must adapt your wit to your rhetorical situation. Know your audience. Just like you wouldn’t crack a dead baby joke at a pro-life convention, you might not want to trot out a side-splitter in a serious research paper for a humorless professor. Freshness¸ though, is adaptable to any rhetorical situation. We always enjoy hearing something from a new perspective. In terms of a research paper or analysis, freshness might help you put a new spin on your analysis.

And everything in moderation. Freshness is a flourish intended to surprise your reader, not an enterprise to be taken on once a sentence. Works that attempt the latter are called “groaners” and promptly cast into the fire.